|

|

Contents

Report of the Solidarity Observer Mission for East Timor (SOMET)On the

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The 2007 Presidential elections are the first national elections conducted according to Timor-Leste’s own laws. Through both the first and second rounds of this election, Timorese voters have shown their understanding of and commitment to peaceful democratic processes, notwithstanding the violence which began last year and the many dire warnings of threats of violence. Once again, Timor-Leste’s electorate has refused to be intimidated from exercising its franchise.

By and large, the voting processes went smoothly, and steps were taken after the first round to correct problems noted by SOMET and others in the second round. While there were still some relatively minor irregularities, we believe that the final results reflect the wishes of the citizens of Timor-Leste.

We are encouraged by the conciliatory tone of the post-election statements of both the winning candidate, José Ramos-Horta, and the conceding candidate, Francisco Gutteres (“Lu-Olo”), and their appeals for national unity and peace after the election. It was unfortunate that this was not the prevalent pattern during the campaign, which was tarnished by language and behavior that promoted division and disrespect, rather than cooperation and the need to work together. We are hopeful that campaigns in the future will focus more on substantive policies and visions for the country and less on accusations and recriminations against adversaries.

In the first round, we noted wide variations in the poll results among different areas of the country. Regional variations were again observed in the second round, with Lu-Olo receiving his strongest support in the three eastern districts, while the remaining ten districts gave substantial majorities to Ramos-Horta. We hope that all parts of the nation will now unite behind the President-elect and that citizens in all areas will receive equal consideration regardless of how they voted.

Voters clearly understood what they were choosing and felt free to express themselves through the ballot. With the elimination of voters’ first choice of candidate in seven of the thirteen districts for second round balloting, they then demonstrated their ability to consider the merits of the two remaining candidates and make an informed choice. The losing first round candidates played an active part in the second round, with five endorsing Ramos-Horta, and the sixth endorsing Lu-Olo.

For this first national election conducted by Timor-Leste authorities, many regulations and procedures had to be created for the first time.

Our teams observed that improvements made for the second round resulted in a much smoother, more efficient and less confusing process. Although some inconsistencies in the rules and gaps in implementation and enforcement remain, we congratulate all involved in designing and conducting the process and commend the considerable efforts to resolve problems. We anticipate that the administration of the Parliamentary election on 30 June will benefit greatly from the experience with the two Presidential rounds.

|

|

Electoral regulatory framework

1. Independence of the Technical Secretariat for Election Administration (STAE)

The Technical Secretariat for Election Administration (STAE) is a government agency under the Ministry for State Administration that is responsible for administering elections. The overall framework for how elections are to be conducted is established by the National Electoral Commission (CNE), an independent commission. In SOMET’s report on the first round, we recommended that future elections be administered by an independent agency that is not under the jurisdiction of any government ministry. STAE significantly improved its performance in the second round, but we continue to believe that its independence from government would be an important step toward ensuring that future elections are free from partisan interference.

2. Stability of the regulatory framework

During the first round, last-minute changes and inconsistencies in the regulatory framework led to staff and voter confusion and many errors on election day. Although a new CNE regulation was issued only two weeks before the second round, most of its contents were to clarify or address deficiencies in the first round legal framework. This improved the electoral process, rather than making it more difficult.

Experience from the two rounds of the Presidential election indicates that the timely adoption of regulations, policies and materials allows more time for training of staff, voter education and candidate preparation; lessens confusion among all participants and provides for a more orderly election process. Remaining inconsistencies and gaps between regulations, codes of conduct and training materials should be addressed well before 30 June, and communicated clearly to all staff, observers and fiscais (party/candidate delegates)[1].

3. Approval of ballot

In contrast with the first round of the Presidential election, the ballot format was established well in advance of the second round, which facilitated both voter education and distribution of materials.

4. Disenfranchisement

During the first round, SOMET noted that the Constitutionally-guaranteed right to vote was violated for prisoners, homebound or hospital-bound voters, citizens alleged to have mental deficiencies and Timorese citizens who were abroad on Election day. These deficiencies were not addressed in the second round. We note that amendments to the law on Parliamentary elections passed on 16 May 2007 provides for prisoners and hospital patients to vote.

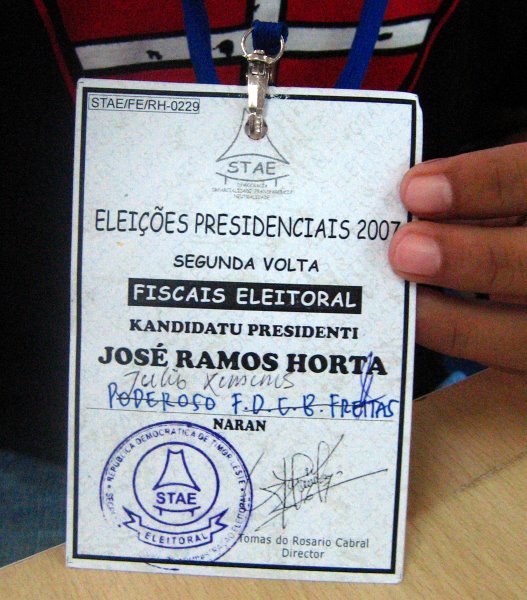

5. Passes for candidate agents and observers

During the first round, SOMET and others noted many problems with excessive numbers of fiscais (candidate and party agents), as well as passes for “Party Observer”, which STAE issued at the last minute without legal justification. We were gratified to see that this problem was greatly reduced during the second round.

Previously-issued passes, especially the extra-legal ones, were not valid during the second round, and we observed very few people trying to use them.

6. “Livre Acesso” passes for government officials|

|

|

|

Baucau: Fiscais IDs are issued to a particular individual, not to be transferred. |

In the first round, STAE issued “Livre Acesso” (free access) passes to Timor-Leste government officials, which were also without any basis in law. We were pleased to observe that no such passes were evident during the second round of voting.

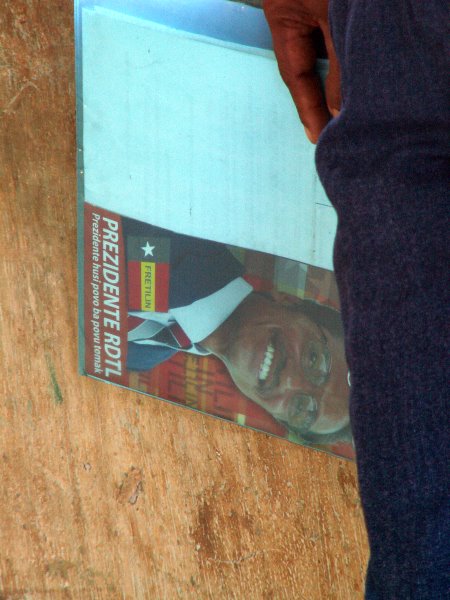

SOMET had limited capacity to observe campaign events for the Presidential election. We noted that the campaigns were less animated for the second round than for the first. No major conflicts between candidates’ supporters were observed during the second round campaign.

Candidates sometimes made promises about matters that do not fall within the powers of the office of President. More care should be taken to restrict promises to areas that they would have control over as President.

For several events that we intended to observe, we found that times and locations had changed, which made observation more difficult. The party representatives we discussed this with explained that this was a result of logistical problems they faced in organizing events.

We observed a public event the night before the election in one polling center aimed at encouraging people to maintain peace and order. Nevertheless, one speech at that event implied preference for one of the candidates.

Despite many accusations of vote buying by both campaigns, SOMET confirmed only one such occurrence. In this instance, village chiefs were given cigarettes and petrol by one of the parties with a promise of additional money if they voted for their candidate.

One of the major issues during the campaign was the financial assets of candidates. There are no regulations requiring candidates to declare their assets, but a public disclosure requirement would assist voters to make assessments of candidates’ claims against their opponents.

Voter education

In one district, observers were told that the voter education period was only one week. This did not allow sufficient time for education staff to cover many remote parts of their areas to ensure that voters were familiar and comfortable with the voting process. Besides training voters on the technical aspects of voting, we feel there should also be broader civic education about their participation in elections.

Guarding of sensitive materials

In two districts in the second round before election day, observers saw boxes containing sensitive materials (ballots, stamps and registration material) stored in unlocked rooms with no one guarding them. There was nothing to prevent unauthorized persons from entering the rooms. Unattended boxes were also observed between the closing of voting and the beginning of counting. One group of national police guarding ballot boxes prior to transport had allowed fiscais into the room with them.

In one polling center, a public event was conducted the night before with four parties present, although sensitive materials were stored in one of the rooms.

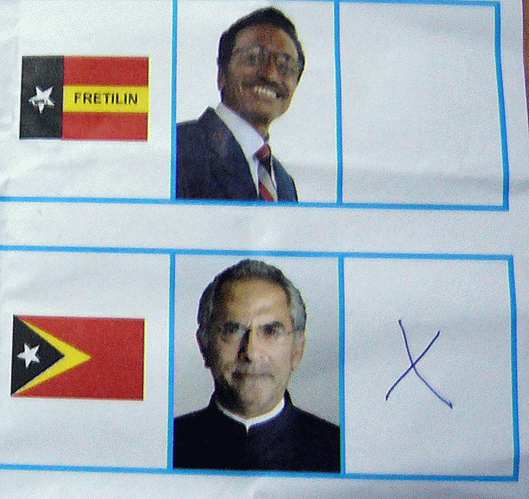

Printing of ballots

In two polling centers in the second round, SOMET observed printing errors on ballots. One error led to well-intentioned voters having their ballots disqualified during the counting process. The ballots contained a printing mark that could be interpreted as a Lu-Olo vote. Votes for Ramos-Horta appeared to have marks for both candidates and were counted as null until the printing error was detected. This did not affect the election results, due to the large difference in votes between the two candidates. However, a similar error could make a difference in the number of seats a party wins in the Parliamentary election, which is by proportional representation.

|

|

|

The mark on the star on the Fretilin flag caused some ballots like this to be rejected as invalid. (Lautem) |

Our observations on election day

Fiscais (party/candidate delegates)

In the first round, the presence of party agents (fiscais and “Party Observers”) was the dominant feature of many polling stations SOMET visited. We observed many more agents than were legally allowed, and they often engaged in inappropriate actions and/or concealed their identities. With the elimination of the “Party Observer” accreditation and fewer fiscais in the second round, the situation at the polling stations was much improved.

1. Number of fiscais in polling stationsThere were inconsistencies in the polling stations we visited in the second round as to how many fiscais were allowed. Polling staff were often not active in enforcing the Code of Conduct for Delegates of Candidacies and Delegates of Political Parties or Party Coalitions, which limits the number of fiscais present in polling stations and District Tabulation Centers to one per candidate. Sometimes only one fiscais per party was admitted, sometimes two, and we occasionally observed three or four, as well as fiscais with obsolete credentials from parties and candidates who were not on the ballot during the runoff.

2. IdentificationAs in the first round, fiscais often failed to display their IDs appropriately. In one polling center, a fiscais had the candidate’s photo on the back of the ID card.

3. Interference in the voting processDuring the first round, fiscais were often pro-active, directing voters through the process when polling staff were inattentive. Although we observed scattered instances of this in the second round, in general polling staff were more helpful, and fiscais only watched, rather than actively engaging voters. However, we did observe some fiscais checking voter IDs and discussing eligibility of voters with identification officers. Fiscais (and sometimes other people) were often standing just outside the polling centers, interacting with voters waiting in line, occasionally replacing or supplementing queue control processes. Inside one polling center, a fiscais prominently displayed Lu-Olo campaign materials on both sides of a notebook he was carrying.

|

|

|

|

Viqueque: Fiscais positions himself between voters and voting booths. |

Viqueque: Campaign material displayed by fiscais in polling station. |

With 14 parties and coalitions on the Parliamentary ballot, it will be critical for polling staff to manage the polling stations to prevent large numbers of fiscais from disrupting the voting process. Our recommendations include several measures to accomplish this.

Interference by unauthorized individuals

|

|

|

|

Manatuto: Chefe do Suco recording names of people as they leave the polling station. |

The presence and interference of high-level government officials during the voting process in the second round was less than in the first, a significant improvement. However, SOMET observed one Minister without election credentials attempting to interfere with the work of observers from just outside a polling center; she later entered a polling station during counting. In another district, we observed another Minister whose behavior was entirely appropriate.

In another polling center, the local chefe do suco set up a table just outside the center, checking IDs and taking down names of voters as they left the polling station.

SOMET also witnessed a leader of a rebel faction during the political and security unrest of 2006 assertively proclaiming his presence and authority in a polling center, intimidating staff and observers.

Voting process

|

|

|

|

|

Baucau: Voters lined up to wait for the polling station to open at 7:00 am.. |

In the first and second rounds, the majority of both polling staff and voters were familiar with voting procedures. In most cases, staff appeared to be well trained and administered the process efficiently. On the whole, staff were able to ensure the right of individual voting, the secrecy of the ballot and the overall integrity of the process. Significant improvements in the voting process were noted by SOMET observers in the second round that made voting more efficient and better regulated. The following issues were noted in the two rounds of voting.

1. Queue control

Queue control at the polling stations was generally better organized in the second round than in the first. Queuing areas were well defined and controlled by the queue controller. There were fewer instances of disorderly crowds or of unauthorized people assuming queue control functions than noted in the first round. There were fewer complaints about waiting times and, in most cases, an orderly flow of voters was maintained inside the polling station.

2. Checking fingers for ink

|

|

|

|

Viqueque: Polling workers were conscientious about checking for inked fingers, but not everywhere. |

The inking of fingers after voting is a check against double voting. Identification officers are required to verify that people coming in to vote do not already have ink on their fingers. In the first round, all SOMET observers attended locations where voters’ fingers were not being checked for ink. In the polling stations observed by SOMET in the second round, only about half of identification officers checked for ink. In the Sixth Report of the Certification Team for the 2007 Parliamentary and Presidential Elections in Timor-Leste (23 April 2007), the Team states, “… the use of ink remains a critical element of the electoral process, and the need for the correct implementation of the procedures surrounding its utilization should be strongly reinforced, including by additional training.” Although the punching of voters’ cards provides a second check against double voting and SOMET observers did not report any direct knowledge of anyone voting twice, the failure of many identification officers to check for ink remains a deficiency in the voting process.

3. Voter identification procedures

The identification of voters at the polling stations generally proceeded efficiently and no major problems were reported in the second round. Problems observed in the first round such as voters bypassing the identification staff and mistakes in record keeping were not noted in the second round.

4. Perforation of identification documents

Rule changes concerning perforation of the new plastic voter registration cards caused some confusion among staff in the first round, and some voters’ cards were not punched. These problems appear to have been alleviated and no major issues with perforation of cards were observed in the second round.

5. Guidance to voters

SOMET observed that some ballot paper issuers in the first round did not provide guidance to voters on how to mark the ballot and where to deposit it. As a result, some voters were confused and party agents were providing information to voters that should have come from polling staff. In general, observers of the second round did not see ballot paper issuers providing guidance to every voter, but most voters were familiar with the process and did not appear to require it.

6. Marking fingers with ink

In the first round, SOMET observed isolated instances of voters leaving the polling station without having their fingers inked. In the second round, the practice of marking fingers was generally good, although we noted a few inconsistencies about which finger to mark and some lack of vigilance on the part of the ballot box controller. Sometimes only small marks were made on finger tips, which were not readily visible, in violation of regulations.

7. Checking polling booths

In the first round, some extraneous items were found left in polling booths and ballot papers on the floor. Observers did not report this in the second round but we saw very little checking of booths by polling staff.

8. Polling staff wearing visible credentials

All polling staff were issued identification credentials, T-shirts and hats. In the first round, observers noted that sometimes credentials were tucked into pockets, hats removed and shirts covered or removed. Although staff showed credentials to the observers when questioned, their function was sometimes not identifiable to voters. With party agents sometimes stepping up to perform staff functions, this created confusion as to who had a legitimate role. In the second round, SOMET observers noted staff members in many of the polling stations whose credentials were not visible. It appears some additional training is required to emphasize the importance of staff being identifiable during the entire voting and counting process.

9. Voter access to polling stations

In both the first and second rounds, the vast majority of polling stations were set up to provide easy access to voters. In one case, the polling staff did not permit a blind voter to take a relative to assist her in the booth, requiring fiscais from the two candidates to assist her instead.

10. Observer access to polling stations

In one instance in the first round, observers were denied access to a polling station that had been set up with the voting booths inside a classroom and the rest of the station outside. Voter identification, issuing and depositing of ballots and inking of fingers were carried on outside.

In the second round, one brigada[2] advised observers that only fiscais were allowed to observe the opening of the polling stations. Team members entered the stations anyway and were not challenged. Observers in one place were also advised that they would not be permitted to re-enter a polling station once they had left it, but this was not enforced.

11. Early closing of polling stations

In the second round, we saw a poll closing before the designated closing time of 4:00 pm but fiscais and observers were present to witness the opening of the ballot box. In another case, observers arrived at 4:10 but were not admitted until 4:35, when the ballots were spread out on the table. If polling stations close earlier than the designated time, fiscais and observers may not be able to ensure that they are present to witness the contents of the boxes as they are opened. This makes the process less transparent.

|

|

Many polling stations were located outdoors. (Baucau) |

12. Polling stations outside classrooms

In two districts during the

second round, observers saw polling stations in which only

the voting booths were inside classrooms and the staff and

ballot boxes were outside. Fiscais were allowed in

the classroom but, at one point, only one fiscais was

in the room with voters, with no one else (polling staff or

observers) to monitor what was going on.

|

|

|

|

Lautem: Women polling staff were usually outnumbered by men, but not here. |

13. Gender balance of polling staff

In the first round, SOMET observers noted that the polling staff included many women and some stations had a 50-50 gender balance. In the second round, with five polling staff members per station, twelve of 37 reported had at least two men and two women; 24 had fewer than two women; and one had fewer than two men. In 32 polling centers reported, 23 brigadas were men and nine were women. We commend the efforts to achieve gender balance of polling staff and encourage further efforts to recruit more women. Staff at one polling station said that more women may be recruited if there was training at the district level, rather than in Dili, so that it would be easier for them to meet their family obligations.

14. Polling staff concerns

Dissatisfaction was expressed in the first round by some staff who felt they should receive more compensation. The election law and regulations require one half of the brigadas in each district and one half of the presiding officers in each polling station to take part in the district tabulation process. SOMET recommended that those who were chosen to be there be compensated for another day of work, and in the second round this was done. There were still long hours required of polling staff. A presiding officer questioned at a District Tabulation Center in the second round advised that he had worked from 6:00 am to 2:00 am on election day and from 8:00 am to 5:00 pm the next day until the district tabulation was complete. In the second round, polling staff in one district were threatening to strike for further increases before the election and, in another, seven staff resigned the day before the election because they said they did not receive enough training, but compensation may also have been an issue. In the latter case, STAE responded swiftly. Within less than two hours, SOMET observed that replacement staff were being trained on site.

15. Shortage of polling stations

In one area, some polling stations considerably exceeded the 1,000 voter maximum benchmark, which caused longer queues, a shortage of ballots and more time required for counting. Some adjustment to the number of polling stations could be made using voter turnout data from the Presidential election.

Counting process

During the first round SOMET noticed a number of violations of regulations, questionable practices and inconsistent procedures. Of our five recommendations, two were at least partially adopted for the second round – these being that: each polling station in a polling center should proceed with its counting simultaneously, and counting should take place inside the polling station. Three others have not been adopted. The counting of ballots is still not conducted according to the regulations; ballots containing extraneous marks or tears are not counted as valid even when the choice of the voter is clear; and in some polling stations, the lighting is still considered inadequate.

Counting has improved considerably since the first round. National observers and fiscais from both candidates were present in most of the stations observed by SOMET. The following is a summary of our observations through the first and second rounds:

1. Counting Outdoors

In the first round, SOMET observed counting at polling stations taking place outdoors to allow the public to observe. Although this made the counting more transparent, it is not in the regulations and may compromise the integrity of the counting process. In the second round, this problem was not encountered in any of the 19 stations where SOMET observed counting.

2. Unauthorized persons present at counting

The presence of unauthorized individuals in the polling stations during counting was a concern in the first round. In the second round, the control appeared to be better, with the exception that the number of fiscais allowed to observe the count was more than that allowed by the Code of Conduct. In many cases hundreds of spectators were outside the station. They were noisy but usually good-natured. However, in one case a group of youths shouted that they would burn down the building if their preferred candidate (José Ramos-Horta) did not win.

At one station, a government minister was present during the counting process. In another, several unauthorized or inadequately identified people were present during the count.

3. Counting in the dark

The need for better lighting to be provided for polling staff was noted in the first round and this was still noted as a problem in the second round.

4. Confusion about invalid (null) ballots

In both the first and second rounds, there were a number of disagreements as to whether a ballot should be labelled “invalid.” Article 37 of the Regulation on Polling and Result Tabulation Procedures for the Second Round of Presidential Elections states that “A ballot paper clearly showing the intention of the voter expressed by the mark made by him/her in the space identifying a candidate shall be considered a valid vote.” However, Article 39 states that a ballot should be considered null if “c) It features any cut, drawing, erasure, or word written on it; d) It features any word or mark allowing the identification of the voter.” Clarification of the regulation and further training both of polling staff and voters should be carried out.

|

|

|

Manatuto: Correct - ballot box emptied before counting begins. |

Dili: Wrong - counting directly out of the box. |

5. Incorrect counting procedure

Articles 36-41 of the Regulation on Polling and Result Tabulation Procedures for the Second Round of Presidential Elections require the following steps to be taken for the counting of ballots:

-

Remove all ballots from the box, unfold them and place them on the table with their backs up, checking for stamps and signatures

-

Count the total number of ballots and register them in the Acta

-

Read aloud the vote, showing it to those in attendance

-

Put ballots into appropriate piles for each candidate, invalid and blank

-

Count and stamp invalid and blank votes

-

Count the valid votes for each candidate

-

Put disputed votes in the appropriate envelope

-

Count the disputed votes

-

Record the counts on the Acta and seal the ballots in the appropriate envelopes

This procedure was not followed in most polling stations where SOMET observed the count. In most stations tabulation was focused on a wall chart. The total for the two candidates was then added to that of invalid, blank and disputed ballots and this was taken to be the total number of voters. This was compared with the list of people who voted. Sometimes the two did not agree. In most such instances, the presiding officer did not recount the ballots to reconcile the figures.

Moreover, in one case, José Ramos-Horta’s vote was not counted. It was estimated from calculating the difference between the sum of Lu-Olo’s vote and the blank, invalid and contested ballots with the number of signed-in voters.

In both rounds, some stations unfolded ballots and counted them one at a time directly out of the ballot box rather than unfolding all face down, and putting them in bundles of fifty prior to examining each one.

The CNE’s announcement of the preliminary results of the presidential run-off elections 345/RE-CNE/V/2007 (14 May 2007) stated that most of the 126 complaints it received were about the counting process at the polling stations.

6. Incorrect procedure - unused ballot papers

In at least one polling station the presiding officer did not announce audibly the total number of unused ballots after stamping them; merely entering the number in the Acta. In one case, unused ballots were left in the polling station.

7. Handling of envelopes

Many stations did not seal the envelopes properly, often because of inferior quality glue. Another common error was forgetting to write numbers (including zero) on the envelopes for null and blank ballots. The valid vote envelope is too small if there are more than 700 ballot papers.

8. Gender data

Although all polling staff collected data on the numbers of male and female voters, only some presiding officers posted them at polling stations. Article 41.8 of the Regulation on Polling and Result Tabulation Procedures does not require the posting of gender data, but such data is of great interest to many voters.

Amendments to the law on the Parliamentary election provide for counting at the district center, rather than in polling stations. SOMET is concerned that this will reduce the transparency of the counting process and promote suspicions of manipulation. Timor-Leste citizens take a serious interest in their electoral process, as demonstrated by large numbers gathering around polling stations to witness the counting and announcement of the results.

District tabulation

1. Reception tables

|

|

|

|

Manatuto: Processing ballots at district tabulation center, with results projected on wall. |

CNE’s training materials for District Tabulation Centers (dated 5 May 2007) stipulate that there should be four reception tables in the District Tabulation Centers (and five in the more populated districts). In the second round, there were usually two, and in Liquiça and Ainaro, only one. Nevertheless, in Liquiça 37 ballot boxes were processed in just over four hours.

2. Staffing

UNV and Acta assistants were missing at some points. At one station a brigada and presiding officer did not attend the center due to lack of transport.

3. Discrepancies

In most cases, minor discrepancies were corrected manually without recounting the ballot papers. Sometimes the ballots were recounted. The Regulation on Polling and Result Tabulation for the Second Round of Presidential Elections does not authorize corrections to the counts to be made at the District Tabulation Center.

4. Acta Final and Acta Conjunta

Neither of these district documents included data on the number of male and female voters in each polling station and the entire district.

5. Role of observers

At one center some international observers were carrying on disruptive conversations. Although they complied with CNE requests to be quieter, the conversations soon became louder again. National Tabulation Center

1. Unsealing and sealing procedure

In the second round, 10 ballot boxes containing Actas, envelopes with invalid and disputed ballots were opened at the National Tabulation Center in Dili so that the Acta could be scanned. This was done before the national tabulation. This procedure reduced the transparency of the process, as there were no fiscais or observers present. Moreover, the seals put on to ensure no tampering during transport were cut. Resealing was necessary and observers were not able to note down the numbers. Police and security forces

|

|

|

|

Manatuto: Police officer in polling station during counting, instead of 25 m away. |

As in the first round, election day was largely free of violence. However SOMET observers in Viqueque left the District Tabulation Center before tabulation was completed because of a security alert from the American Embassy relating to some shooting during the previous night and one house being set on fire.

On the whole security forces also behaved appropriately. Soldiers from the Australian-led International Stabilization Force (ISF) and the Bangladeshi Special Police Unit (FPU) were less visible than in the first round but nevertheless we encountered them in full battle gear in three districts.

One member of the PNTL (Timorese police under UN command) attempted to enter a polling station to vote with his loaded pistol but obeyed an order by the brigada to leave it with his colleague the regulation 25 meters away. At another station UN police positioned themselves in a classroom next door to the polling station. In one sensitive area, members of the GNR (the Portuguese police rapid response force) were closer than 25 meters.

A Filipino UNPOL (United Nations Police) was checking IDs at the entrance to a compound in Dili and turning away anyone without a voting registration card. During counting at another station, PNTL police were in the room. A UN volunteer informed them they were not allowed to be present and they left.

Reporting election results

During the days immediately after the first round of voting, unofficial and partial results circulated widely without context or explanation. This phenomenon led to many inaccurate predictions of the final outcome and allegations and baseless fears of manipulation when the totals changed after further counting. The results of the second round were quick and decisive and did not lend themselves to uncertainty. As in the first round of the Presidential election, the Parliamentary election will feature many more choices on the ballot, and reporting of partial results may again present challenges.

During the second round no incidents involving journalists were reported and neither candidate complained to CNE about biased media coverage.

On the regulatory framework for elections

1. Future elections should be administered by an independent agency that is not under the jurisdiction of any government ministry.

2. New regulations and a new ballot form for the Parliamentary election should be finalized as soon as possible, at least three weeks before voting day. For elections in future years, we continue to recommend that the regulatory framework be finalized when the date of the election is announced.

3. Parliament, STAE and other responsible authorities should enact legislation and procedures to implement the Constitution’s guarantee that all Timor-Leste citizens 17 years and older have the opportunity to vote.

On campaigning

1.Campaigns should focus on policies, rather than personal attacks or accusations of wrong-doing without evidence.

2.Consideration should be given to requiring candidates to file a public disclosure of their financial assets.

On voter education

1. Sufficient resources and time should be devoted to ensuring that voters are familiar with the voting process. It should be expanded to include civic education.

On guarding of sensitive materials

1.Sensitive materials should be adequately secured and guarded at all times.

On the printing of ballots

1.Good quality control on ballot printing is essential.

2.As a final check, polling center staff should be instructed to examine each blank ballot while counting them prior to the opening of voting.

On the

roles of fiscais (party/candidate delegates) and

observers

1.The number of fiscais should be limited to one per party per polling station at any given time, as required by the Code of Conduct for Delegates of Candidacies and Delegates of Political Parties or Party Coalitions.

2.The total number of fiscais for each party receiving CNE accreditation should not exceed two times the number of polling stations.

3.Credentials for fiscais and observers should be issued at least a week before election day.

4.Legal regulations (in addition to codes of conduct) should define the rights and privileges of fiscais and observers. They should not intervene unless they observe a violation in the law or procedures in the polling station; they should not communicate with voters inside the polling station or at the polling center; and they should not interfere with or “assist” polling staff in their duties.

5.Polling stations should maintain a register of fiscais and observers who enter the polling station, and this task should be integrated into the responsibilities and training of polling center staff.

6.Training for fiscais and polling staff should emphasize the limit on the number allowed in the polling station at any one time, as well as the bans on campaigning or displaying materials within and near polling centers and on communicating with voters.

7.Fiscais should not loiter within 25 meters of the polling center.

8.Polling staff should be empowered and encouraged to enforce rules about fiscais activities, with support from PNTL if necessary.

9.If it is necessary to control the number of observers in polling stations, it should be restricted to two observers per organization per polling station.

10.All fiscais and observers should display their ID cards outside their clothing, hanging from their necks in front of them during the entire process of opening the polling station, voting, closing and counting. Polling station staff should ask people without clearly visible IDs, other than those voting, to leave the polling station.

11.Polling stations should include a list with photo samples of valid fiscais and observer credentials, and staff should admit only those with valid identification.

On the role of government and local officials1.Officials not directly involved in the election should remember that their rights and powers regarding the election are no different from those of all other citizens, and they should not use the election process for their own or partisan purposes.

On polling center staff and the voting process1.All polling staff should wear and display their credentials and identification during the entire process of opening polling stations, voting, closing of polling stations and counting.

2.Polling staff should ensure that voters who have already voted and are not fiscais, observers or accredited media professionals are not allowed in polling centers, in accordance with election regulations.

3.Particular attention should be paid to ensuring that identification officers check all incoming voters’ fingers for ink.

4.Polling staff should check voting booths regularly for materials or marks that should not be there.

5.Voting booths should be visible to polling staff, fiscais and observers to ensure that voting is proceeding according to election laws and regulations.

6.Polling staff should be aware that voters requiring assistance to vote are entitled to be accompanied in the booth by a person of their choice.

7.All polling staff should receive fair compensation for the time that they work.

8.STAE should continue their efforts to improve gender balance among polling staff and consider training at the district level to enable more women to attend.

9.Opening and closing hours should be strictly observed. Observers and fiscais should be present at 6:00 am and no opening procedures should begin before that time. Voting, even for polling staff, fiscais and observers, should not begin before 7:00 am, and polling stations should not close before 4:00 pm. The allowable number of fiscais and observers should not be denied entry at any time.

10.STAE should ensure that there is an adequate number of polling stations to accommodate the number of voters in an area. The maximum number of voters per polling station should not exceed 1,000.

On the counting process

1. All counting of ballots should take place indoors.

2. All counting of ballots should be conducted according to the procedure set out in regulations.

3. Ballots should be accepted as valid if the intention of the voter is clear and voters cannot be identified. The regulations on what constitutes a valid or invalid vote should be made clearer.

4. Polling staff should keep unauthorized individuals out of polling stations during the count.

5. Gender data should be posted with the election results at the polling station.

6. The envelopes containing the cast ballots should be able to be secured robustly and large enough to contain comfortably the expected number of ballot papers.

7. In future elections, consider closing polling stations at 3:00 pm, as almost no voters arrive after that time and it would allow another hour of daylight for counting and transport. Counting procedures should commence as soon as the polls close.

On the district tabulation process

1. There should be an adequate number of reception tables and sufficient staff and space in District Tabulation Centers to accommodate the number of ballot boxes in each district.

2. Legal authorization is required if corrections to the Actas are to be made at the District Tabulation Center.

3. Discrepancies should be corrected by recounting the ballot papers, rather than by arithmetical calculation.

4. Gender data should be reported at the district level.

On the proximity of police and security forces

1. The police forces should stay at least 25 meters from polling stations during polling and counting of votes, unless their assistance is requested by a presiding officer, in accordance with laws and regulations.

2. Military forces should stay out of sight of polling stations, except when called by police in an emergency.

On reporting the results

1.Care should be taken in reporting preliminary results, especially considering the regional variation in voting patterns evident in the Presidential election.

|

First round |

|

| Ernest Chamberlain Christian Donn Craig Hughes Jaana Karhilo Ruby Rose Lora Catharina Maria | Joerg Meier Veronica Pais Charles Scheiner Susan Severin Santina Soares Jill Sternberg |

|

Second round |

|

|

Maria Fatima Sara D. Afonso, Fokupers Marilia da Silva Alves, Fokupers Fransisco Pinto Amaral, Bibi Bulak José Amaral, NGO Forum Secretariat Domingos Soares Babo, NGO Forum Secretariat Robert Crane J.P. Shinta Dewi, Fokupers Christian DonnSelma Widhi Hayati Elinde Kersbergen Mateus de Oliveira Lopes, Bibi Bulak Maria Madalena, Bibi Bulak |

Catharina Maria Joerg Meier Guteriano Neves, La’o Hamutuk Roy Pateman Daniel Pereira, Kadalak Sulimutuk Institute Elisa dos Santos, Fokupers Charles Scheiner, La’o Hamutuk Santina Soares, La’o Hamutuk Jill Sternberg Mateus Tilman, Kadalak Sulimutuk InstituteSilvano Rodrigues Xavier, Bibi Bulak |

Acronyms

CNE - National Electoral Commission (Comissão Nacional de Eleções)

GNR - Republican National Guard (Guarda Nacional Republicana) (Portuguese)

ISF - International Stabilization Force

PNTL - Timor-Leste National Police (Policia Nacional de Timor-Leste), currently under United Nations command

SOMET - Solidarity Observer Mission for East Timor

STAE - Technical Secretariat for Election Administration (Secretariado Técnico de Administração Eleitoral)

UNMIT - United Nations Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste

UNPOL - United Nations Police

UNV - United Nations Volunteer

[1] Candidate representatives are referred to in regulations as “delegates” (“fiscais” in Portuguese) of political parties or party coalitions (Article 67 of the Law of the Election of the President of the Republic (Law No. 7/2006) and the STAE Code of Conduct for Delegates of Candidacies and Delegates of Political Parties or Party Coalitions (March 2007)). We will use the term “fiscais”, which is in most common usage, throughout this report.

[2] Polling center supervisor. A polling center may contain several polling stations, each supervised by a presiding officer.

See also

Report of the Solidarity

Observer Mission for East Timor (SOMET) on the first

round of the Timor-Leste 2007 Presidential Elections (also

in Tetum)

Elections 2007 -

campaigns; results; laws and regulations; observer reports; and other background

|

Make a

monthly pledge via credit card subscribe to ETAN's news listserv on East Timor (it's free) |