|

|

|

Special issue of Tempo magazine

timed for release of The

Act of Killing. |

These axes jockeyed for power,

especially as Sukarno created and

dissolved cabinets with regularity

in the 1950s until the 1959 implementation

of “Guided Democracy,” Sukarno’s

plan for stability that forewent

elections. The military (and its

U.S. backers) and political Islamists

grew concerned over the PKI’s popularity,

and the military became increasingly

belligerent. The PKI, led by firebrand

Aidit, reacted by demanding greater

political power and creating para-military

organizations. The nationalist campaigns

to seize West Papua and confront

Malaysia in the early 1960s were

used to distract Indonesians from

their domestic political and economic

concerns.

|

|

|

Maj. Gen. Suharto, left

front, with Gen. Sabur,

commander of the presidential

guard, October 1965.

|

|

In this context

of political and economic chaos,

members of Sukarno’s Presidential

Guard kidnapped six generals and

a lieutenant on the morning of October

1, 1965. The officers were murdered,

and the kidnappers - calling themselves

the 30th of September Movement -

said they were acting to prevent

an anti-Sukarno coup d’état. A quick

response and counterattack was organized

in Jakarta, led by Major General

Suharto, then the leader of the

military’s Jakarta-based Strategic

Reserve (Kostrad) troops. Within

a day of the coup, Suharto had gained

control of the military and the

PKI was blamed for the kidnappings

and murder, although evidence casts

doubt as to how well-coordinated

the plot was. Observers have also

raised questions about what Suharto

might have known prior October 1,

since he was not targeted and appeared

poised to take quick advantage of

the situation. An above-ground,

legal, popular, and mass-based political

party was criminalized overnight,

with membership punishable by death.

PKI members,

their families, and their associates,

but also other leftists, critics of

the military, ethnic Chinese, and many

others, were rounded up and murdered

or told to report to the government.

Many did so willingly, completely unaware

of the fate that would befall them –

they had done nothing criminal, after

all, and didn’t fear for their safety.

| |

I urge us all to examine ourselves,

and acknowledge that we

are all closer to perpetrators

than we like to believe.

The United Kingdom and United

States helped to engineer

the genocide, and for decades

enthusiastically supported

the military dictatorship

that came to power through

the genocide. We will not

have an ethical or constructive

relationship with Indonesia

(or so many other countries

across the global south)

going forward, until we

acknowledge the crimes of

the past, and our collective

role in supporting, participating

in, and, ultimately, ignoring

those crimes."

-

speech

by Joshua Oppenheimer

accepting BAFTA award

for best documentary

|

The

military, police, and Muslim groups

formed citizen militias to do the

dirty work. In Medan, for example,

as shown in the of

Act of Killing,

local gangsters were recruited to

do the killing. Throughout Sumatra,

Java, and Bali, and to a lesser

extent elsewhere, a bloodbath began.

Rivers were choked with bodies and

flowed red with blood. Canyons became

the sites for group beheadings and

decapitations - one site is

known as the "Ravine of

Tears." The “luckier” ones,

frequently those whose guilt was

in question, were imprisoned and

tortured without trial. Within two

years, hundreds of thousands were

dead. Within six months, some 1.7

million

people were imprisoned. Suharto

assumed the presidency, the PKI

was liquidated, and political Islam

was shunted aside, as the military

took firm control of Indonesia.

Dissent was suppressed in the name

of fighting communism; many others

were too afraid to speak out. Elections

were managed to make sure only Suharto-backed

candidates won. The military dictatorship

would last until Suharto’s resignation

in 1998.

Former

political prisoners and their families

remained marginalized for decades; their

association noted on their ID cards,

employment opportunities closed off

to them. Although a few victims’ groups

have emerged since the start of Indonesia’s

democratic transition, they also remain

marginalized and threatened. Their meetings

are attacked and their members accused

of engaging in communist activity. Indonesia’s

official National Commission on Human

rights (Komnas HAM) recently investigated

the killings and

published a report. Although its

scope and budget were limited, it found

horrendous abuses associated with the

anti-communist purge. The commission

recommended either non-judicial action

to restore a sense of justice for the

victims or that the Attorney General

proceed with cases. The Attorney General,

Darmono,

said he could not act because "The

1965 rights violations are beyond (the

scope of) the existing law." No

action has yet been taken on the report.

U.S.’s dark history

in the Indonesia’s mass violence

Although the

political struggle and the resultant

mass violence were the culmination of

decades of conflict among Indonesians,

the U.S. sanctioned, encouraged, and

assisted the killings. The U.S. government

was concerned that Indonesia might fall

to communism as events in Vietnam, Cambodia

and Laos (as well as Latin America)

were heating up.

|

|

|

Presidents Kennedy and Sukarno,

Andrews Air Force Base,

Suitland, Maryland, April

1961. Photo JFK Library

and Museum. |

|

The U.S. role

in early Indonesian politics dates

back to the revolution, when it

assisted in negotiations on independence

between the Dutch and Indonesian

nationalists. Less than a decade

later, the US was sending arms and

support to rebels in Sulawesi and

Sumatra who were fighting the central

government in an effort to topple

Sukarno.

The assistance included

sending U.S. bombers from their base

in the Philippines to attack targets

in Indonesia. This ended after U.S.

pilot Allen Pope was captured on May

18, 1958. His plane was shot down after

bombing a church in Ambon. Without U.S.

support, the rebellion was quickly crushed.

Despite the U.S. role in the rebellion,

anti-Sukarno military officers continued

to discuss with the U.S. their mutual

goal of toppling Sukarno and undermining

the PKI.

The Kennedy administration

facilitated the turnover of resource-rich

Western New Guinea (West Papua) by The

Netherlands, first to the UN and then

Indonesia, against the wishes of its

inhabitants. This was done to endear

itself to Sukarno and the Indonesian

military and

perhaps for economic reasons.

The U.S. stepped

up military aid and its training of

Indonesian officers and police. In the

early sixties, U.S. security assistance

focused on “civic action: as a nation-building

exercise, as a counterinsurgency strategy,

and, not incidentally, as a front for

covert operations aimed at the PKI.”[i]

Prior to the events of October 1,

Indonesian military officers speculated

that a failed coup attempt by the

PKI would provide a perfect pretext

for eradicating the party, and this

idea was shared with the US embassy

staff, who encouraged it and pledged

support. In January 1965, the U.S.

ambassador reported to Washington

that the Indonesian army was “developing

specific plans for takeover of the

government moment that Sukarno steps

offstage.” The cable continued that

some top military commanders were

prepared before Sukarno’s death

should the PKI form an armed civilian

militia. They would act in a way

that appeared to leave Sukarno in

charge.

[ii]

| |

The

New York Times’ James Reston

called the “savage transformation…

a gleam of light in Asia.”

Richard Nixon wrote "containing

the region's richest hoard

of natural resources, Indonesia

constitutes by far the greatest

prize in the Southeast Asian

area."

|

As events unfolded

in the days following October 1, American

diplomatic and intelligence staff encouraged

the eradication of the PKI, and closely

monitored the Indonesian military’s

actions. Robert Martens, head of the

US embassy’s political affairs bureau,

gave the army thousands of names

of suspected PKI members. U.S. officials "checked

off the names of those who had been

killed or captured.” The embassy also

transferred cash to leaders of the anti-PKI

movement. As soon as Suharto’s command

was consolidated, the US and other Western

countries pledged millions of dollars

in economic assistance, and Suharto

reversed Sukarno’s policy by opening

the country up to foreign investment.[iii]

The New York Times,

quickly praised the coup. In a page

one story on October 11, reporter

Max Frankel wrote that there was

“hope where only two weeks ago there

was despair about the fifth most

populous nation on earth, whose

103 million inhabitants on 4,000

islands possess vast but untapped

resources and occupy one of the

most strategic positions in Southeast

Asia.”[iv]

In June 1966, the Times’ James Reston

called the “savage transformation… a

gleam of light in Asia.” Time magazine

hailed Suharto’s takeover as “the West’s

best news for years in Asia.”[v]

Later,

Time Inc. sponsored a closed-door "Indonesian

Investment Conference" in Geneva

in November, 1967, the first such conference

since Suharto seized power.

In 1967, Richard

Nixon argued that "The U.S.

presence... was a vital factor in the

turnaround in Indonesia, where a tendency

toward fatalism is a national characteristic.

It provided a shield behind which the

anti-communist forces found the courage

and the capacity to stage their counter-coup

and, at the final moment, to rescue

their country from the Chinese orbit.

And, with its 100 million people, and

its 3,000-mile arc of islands containing

the region's richest hoard of natural

resources, Indonesia constitutes by

far the greatest prize in the Southeast

Asian area."

By the end of 1968,

the CIA was downplaying Suharto’s

brutality, writing in a classified National

Intelligence Estimate that “the Suharto

government provides Indonesia with a

relatively moderate leadership.” Adding

that “There is no force in Indonesia

today that can effectively challenge

the army's position, notwithstanding

the fact that the Suharto government

uses a fairly light hand in wielding

the instruments of power.”

Later analyses of the violence showed

its often chaotic nature, despite

being organized from the top. Hermawan

Sulistyo’s PhD thesis

[vi],

for example, shows that the anti-communist

bloodletting was used by various

groups to eliminate their enemies:

landlords, tenants, ethnic Chinese,

debtors, etc. All one had to do

was accuse someone of being a member

of the PKI or a sympathizer, and

extrajudicial death was the result.

Those who were not killed on the

spot, frequently because the “evidence”

of their ties to the PKI was egregiously

spurious, were sent to prisons or

exiled to islands that became prison

camps, such as Buru. This was the

fate of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Indonesia’s

best known author, who detailed

his experience in his memoir and

suffered persecution until the end

of the Suharto regime.

After-effects

Suharto

had consolidated his rule by early 1966,

and Sukarno had been shunted aside.

The tight bonds forged by the CIA and

diplomatic staff in Indonesia remained

during Suharto’s tenure (1965-1999).

U.S.-based multinational corporations

were free to plunder the country – it

is said that the first MNC to engage

with the Suharto government, Freeport

McMoRan, wrote its own contract with

immensely favorable terms – making sure

Suharto received his cut.

Time Magazine wrote in 1999 that

it “found indications that at least

$73 billion passed through the [Suharto]

family's hands between 1966

and last year." The New York

Times

reported that in 1989 the CIA

estimated Suharto's wealth at $30

billion. Freeport is Indonesia’s

largest foreign taxpayer. National

Security Adviser Henry Kissinger

told President Richard Nixon

in 1968 that the manner in which

Indonesia was to seize the territory

– in a

sham plebiscite that remains

widely condemned – was to be off

limits in discussion, essentially

giving Suharto a free hand. (Between

1988 and 1995,

Kissinger was paid $500,000

per year to be on the board of Freeport

McMoRan. And the American military

ramped up its engagement, free from

the constraints imposed under Sukarno.

In early 1976, soon after Indonesia

brutally invaded East Timor, a

State Department official said, "the

United States wants to keep its

relations with Indonesia close and

friendly. It is a nation we do a

lot of business with." Nearly

two decades later, a White House

official

called Suharto “

our

kind of guy” after the dictator

met with President Clinton. Suharto,

The New York Times wrote “

has

been savvy in keeping Washington

happy.”

The list of egregious

human rights violations during

Suharto’s New Order is lengthy,

including the “mysterious shootings”

incidents of the early 1980s, the 1984

Tanjung Priok massacre, and the persecution

and killings in West Papua and Aceh.

Among the most egregious was the 1975

invasion of former Portuguese colony

and newly declared independent state

Timor-Leste (East Timor), where up to

one-third of the population died in

the years following the invasion. Throughout

all of these human rights disasters,

the United States remained firmly on

Suharto’s side, pledging financial and

political support, encouraging investment,

and perhaps most troubling, providing

military aid and training, at times

contrary to the US Congress’ wishes

and in violation of US law. At

a State Department meeting on Timor-Leste,

one official told

Secretary

of State Kissinger how “happy [Indonesia

is] with the positions we have taken.

We’ve resumed, you know, all of our

normal relations with them…”

Kissinger responds: "Illegally

and beautifully,” a reference to the

fact that he had ignored the requirement

to suspend military assistance to Indonesia

for using U.S. weapons to invade its

neighbor. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, former

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations,

bragged in his memoir of his ability

to stymie effective UN action on the

invasion of Timor-Leste.

The U.S. government would occasionally

condemn some of Indonesia’s human rights

violations, but its actions spoke louder:

during the 32-years of the Suharto dictatorship

the U.S. provided more than a billion

dollars' worth of weapons and other

military equipment. The Pentagon also

provided

training

highly valued by the Indonesian

military . Many of Indonesia’s most

notorious generals were trained in the

U.S. Only in the 1990s,

facing

congressional action and grassroots

pressure, did the administrations

start to restrict access to U.S. training

and weapons. The U.S. has never

apologized for its support of mass murder

and dictatorship in the aftermath of

the 1965 events, nor has it expressed

any regret for its support of Suharto’s

brutal military dictatorship that followed.

|

|

|

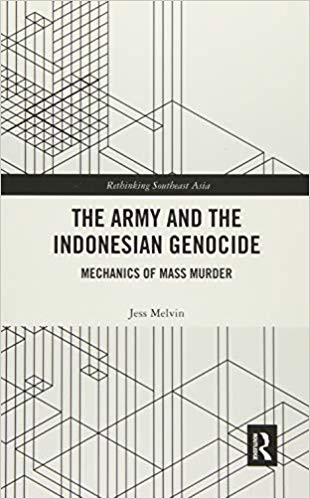

Adi Rukun from The Look of

Silence. |

|

Indonesian relatives of those “tainted”

with ties to the PKI – however spurious

they may be – remain victims of abuse

in Indonesia and portrayed as enemies

of the state.

The experience of

Adi Rukun, the protagonist of

The Look of Silence, is

the

latest example. Out of concern for their

safety, he has chosen voluntary exile

and his family has moved elsewhere in

Indonesia, thousands of miles from their

home. The Indonesian crewmembers

of both films have chosen to remain

anonymous for their own security. Victims

of Suharto’s genocidal policies in

Timor-Leste and

West Papua – as well as victims

of other abuses – have yet to see justice.

As you watch the films Act of Killing

and The Look of Silence, ETAN

asks you to think of the victims and

to reflect on the role of the U.S. in

perpetrating and perpetuating these

crimes against humanity. The

ability of the perpetrators to make

their version of the story the official

one allows them to enjoy impunity for

their actions, an impunity that UK-based

human rights group TAPOL calls an obstacle

to Indonesia’s ongoing democratization.

And a thorough accounting of events

would also hold responsible figures

in the United States and other Western

countries who encouraged and supported

the violence.

As Indonesia and Timor-Leste specialist

Brad Simpson pointed out in a recent

article in

The

Nation, the U.S. role in the violence

portrayed in the films makes it our

“act of killing, too.

Take Action

ETAN is urging the U.S. government

to take two immediate steps: 1) Declassify

and release all documents related to

the U.S. role in the mass violence,

including

the CIA’s so-called “job files.” These

describe its covert operations. 2) The

U.S. should formally acknowledge its

role in facilitating the 1965-66 violence

and its subsequent support for the brutalities

of the Suharto regime. See

more action ideas here.

|

Order

from Amazon,

Support ETAN |

|

|

|

|

|

The

East Timor and Indonesia

Action Network

(ETAN)

was founded in 1991. ETAN

s a U.S. based grassroots organization

working in solidarity with the peoples

of Timor-Leste, West Papua and Indonesia.

ETAN educates, organizes, and advocates

for

democracy, human

rights and justice. Website:

www.etan.org. Twitter:

@etan009.

[i] Simpson,

Brad, Economists with Guns:

Authoritarian Development and

U.S.-Indonesian Relations, 1960-1968,(Stanford:

Stanford University Press, 2008)

p. 75

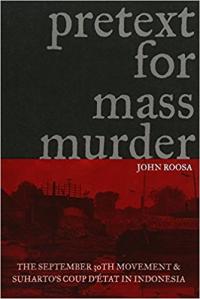

[ii] Roosa,

John, Pretext for Mass Murder,

(Madison: Wisconsin University

Press, 2006) p. 189

[iv] Quoted

in Roosa p. 16

[vi] “The

forgotten years: the missing

history of Indonesia's mass

slaughter, Jombang-Kediri, 1965-1966,”

(ASU, 1997)xxxx

Action

ALERT:

See/Show The Look of Silence and

Take Action on U.S. Support for Mass

Violence in Indonesia

See also