see also:

ETAN Statement

on 2014 Indonesian Election

(July 10)

Download

PDF File

East Timor and Indonesia

Action Network (ETAN)

ELECTION BACKGROUNDER

Indonesia’s Militarized Democracy:

Candidates bring proven records of violating

human rights

Contents

About ETAN

March 2014

-

Although

Indonesia has made strides toward consolidating

its democracy, some of its leading presidential

and vice-presidential candidates continue

to have deeply troubling backgrounds of

gross human rights violations. This report

provides a brief background on Indonesian

democratization and examines some of the

contenders for the nation’s highest political

offices.

|

|

|

Indonesian

voters. Photo

byNatalia Warat/Asia Foundation |

|

Indonesia is in the midst of an election

campaign. On April 9 voters will elect members

to the national and regional legislatures.

Once that election is completed Indonesia

will hold its third presidential election

following its transition to democracy after

32 years of military dictatorship. Candidates

for the July 9 presidential election will

be determined in part by the election for

the People's Representative Council (Dewan

Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR). A presidential

ticket must be supported by a party or coalition

of parties with at least 25 percent of the

vote or 20 percent of the seats in the DPR

election. While many parties have announced

their favored candidates, only two – Golkar

and PDI-P – out of

12 registered national parties are thought

to have a chance at passing the threshold.

The final determination of candidates will

occur after the official DPR results, scheduled

to be released on May 7, when coalitions

of parties may form to put together tickets.

The presidential and vice-presidential candidates

have often come from

different parties.

Current president and former general Susilo

Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) is completing his

second term and is barred by term limits

from running again. For months potential

candidates have been jockeying for support

– from both the general population and from

political parties. Below, we briefly examine

some worrisome candidates, based on their

human rights and military records.

Indonesian

Democracy

and

Democratization

Democratization is a process. When Suharto

was forced from office in May 1998, Indonesia

did not democratize overnight. In fact,

it took a year for the first

nationally contested election, which

eventually brought the Muslim

intellectual Abdurrahman Wahid, popularly

known as Gus Dur, to the presidency.

Today, most Indonesian political parties

are personality-based, with limited platforms.

Parties with major media owners behind them

are thought to have an advantage and in

some areas politics is a family business.

Corruption accusations and convictions have

affected the popularity of several political

parties, including SBY’s Democratic Party

(Partai Demokrat, PD) and the Islamic Prosperous

Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera, PKS).

|

|

Elections do not make a democracy

- elections were regularly held

during the Suharto period, albeit

with little competition and highly

predictable results.

|

And elections do not make a democracy -

elections were regularly held during the

Suharto period, albeit with little

competition and highly predictable

results. And while

elections in Indonesia are now more open

than before, they are merely the most superficial

aspect of democracy.

Meaningful

democracy includes more than electoral competition.

Government should be responsive to people’s

needs and not just the demands of elites.

It should work to ensure equality of opportunity,

minimum social guarantees for the population,

freedom from entrenched corruption in the

economic, political and legal spheres, the

elimination of military influence in politics

and the economy, an end to racism and religious

persecution, and the respect of basic human

rights for Indonesia’s marginalized populations.

Yes, democratization is chugging along in

Indonesia, but when one views the plight

of indigenous West Papuans and the ongoing

impunity of the security forces it is impossible

to think of Indonesia as a mature, consolidated

democracy.

Indonesia has come a long way since 1999.

Timor-Leste is now independent, Indonesia’s

press is much freer, a nervous peace hangs

over Aceh, and some politicians, judges

and business owners have been tried for

corruption. Under President SBY, however,

religious and ethnic tensions have risen,

notably against Indonesia’s Shiite, Ahmadi,

and Christian populations. Repression continues

in West Papua. Local legislatures across

Indonesia have passed discriminatory laws.

Thugs and gangsters from groups such as

the Islamic Defenders Front have provoked

and intimidated minorities, and have literally

gotten away with murder. Military reform

has stalled and even modest efforts to address

past violations of human rights have gone

nowhere.

Indonesia has a long and firm

history of military-trained national leaders.

Since Sukarno, only three Indonesian presidents,

who governed for a combined total of six

years, have not been in the military. Although

having an ex-military president does not

necessarily mean hostility toward democracy,

those who served during the

dictator General Suharto's

New Order period of 1965-1998 became acculturated

to a system in which the military was granted

tremendous political, economic and military

power. Gus Dur’s attempts to check this

power was one of the reasons that his presidency

failed, and many in the military remain

disgruntled with any moves to disengage

them from politics and the economy.

Where Indonesia will be in another five

years – the length of a presidential term

– is difficult to predict. But for those

interested in human rights and democracy,

it is all too easy to envision a rollback

of positive reforms under the wrong president.

That some of the men described below are

serious candidates for Indonesia’s highest

office (and that many others with highly

tainted records play powerful roles in most

Indonesian political parties), speaks to

the country’s failure to confront the violations of human rights on which they

built their careers. This lack of justice

and accountability will only reinforce the

sense of impunity that pervades Indonesia

and undermines its democracy.

Below are potential candidates for

president with deeply troubling human

rights records. Disturbingly, their violations

are viewed positively by some, as signs

of toughness. While their

records have been questioned at times during

their political campaigns, they deserve

constant attention and deeper investigation

as Indonesians go to the polls.

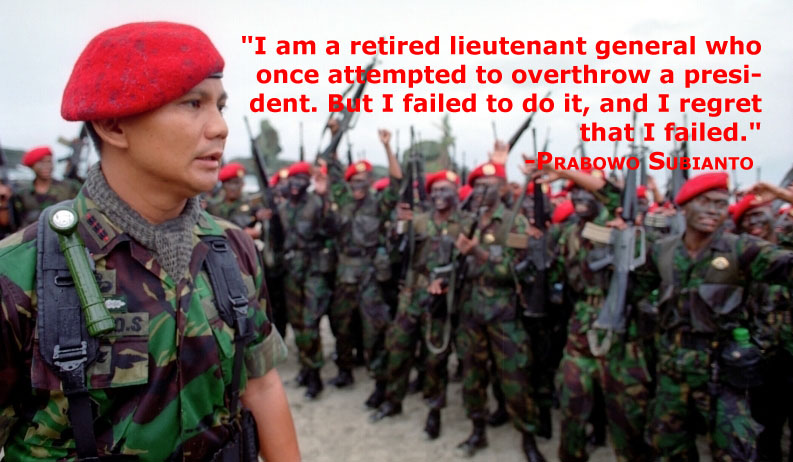

Prabowo

Subianto

Prabowo

spent much of his military career in Indonesia’s

notorious

Kopassus special forces, becoming its

commander from 1995-1998. He now leads the

Great Indonesia Movement Party (Partai Gerakan

Indonesia Raya, Gerindra Party), which is

largely funded by his millionaire brother.

Prabowo had close ties to Suharto during

the New Order (he married and has a son

with Suharto’s daughter Titiek). He

received military training in the U.S.

The Washington Post reported in 1998

that his "ties to the U.S. military are

the closest of any among the U.S.-trained

officer corps." Former U.S. Ambassador to

Indonesia

Robert Gelbard described Prabowo as

“somebody who is perhaps the greatest violator

of human rights in contemporary times among

the Indonesian military. His deeds in the

late 1990s before democracy took hold, were

shocking, even by TNI standards.” Prabowo

spent much of his military career in Indonesia’s

notorious

Kopassus special forces, becoming its

commander from 1995-1998. He now leads the

Great Indonesia Movement Party (Partai Gerakan

Indonesia Raya, Gerindra Party), which is

largely funded by his millionaire brother.

Prabowo had close ties to Suharto during

the New Order (he married and has a son

with Suharto’s daughter Titiek). He

received military training in the U.S.

The Washington Post reported in 1998

that his "ties to the U.S. military are

the closest of any among the U.S.-trained

officer corps." Former U.S. Ambassador to

Indonesia

Robert Gelbard described Prabowo as

“somebody who is perhaps the greatest violator

of human rights in contemporary times among

the Indonesian military. His deeds in the

late 1990s before democracy took hold, were

shocking, even by TNI standards.”

Prabowo served several tours in Timor-Leste,

where he “developed his reputation as the

military's most ruthless field commander”

(Joseph Nevins, A Not-So Distant Horror,

Mass Violence in East Timor, Cornell

University Press, 2005:

61). Among other

actions he was involved in the 1978 capture

of Fretilin leader Nicolau Lobato, who was

shot and killed while in custody. In the

1990s, he organized gangs of hooded killers

known as “ninjas” and the Tim Alfa militia

in Los Palos to terrorize and cow the population.

Prabowo

is also accused of being involved in

the September 1983 Kraras massacre, where

more than 300 people were killed by Indonesian

soldiers, and several East Timorese have

accused Prabowo of torturing them. Prabowo

denies involvement. Release of Prabowo’s

complete military records, including his

and his troops

locations on particular dates, would clarify

his role.

In 1996, Prabowo led a team to secure the

release of environmental researchers taken

hostage by West Papuan guerrillas. He aborted

a planned Red Cross supervised release of

the hostages to prevent his

sister-in-law from getting credit.

According to Ed McWilliams, a former

U.S. diplomat, “The aborted hostage transfer

led to a brutal campaign of reprisal attacks

by the Indonesian military (largely Kopassus)

against highland villages.” This campaign

began with an assault from “an Indonesian

military helicopter disguised to look like

the helicopter that ICRC mediators had been

using” in violation of well-established

international humanitarian law.

|

|

I am a retired lieutenant general

who once attempted to overthrow a

president. But I failed to do it,

and I regret that I failed. -

Prabowo

|

As the tumult associated with the East Asian

economic crisis in 1997-98 threatened the

political legitimacy of the Suharto regime,

Prabowo spearheaded campaigns to kidnap,

arrest, intimidate and torture student activists.

Protesting students at Trisakti

University were killed and wounded by

military snipers.

Prabowo has acknowledged his role in the

kidnappings, but has

said his “conscience is clear.” Convicted

by a court of honor for “exceeding orders,”

Prabowo was forced to retire.

He is also accused of having a central role

in sparking the May 14, 1998 anti-Chinese

riots in Jakarta and other major urban areas.

At the time, Prabowo was head of the Kostrad

(the Army Strategic Reserve) based in the

capital. In 2003, the National Commission

on Human Rights (Komnas HAM)

accused Prabowo of responsibility

“for gross human rights violations that

occurred during the extensive rioting in

Jakarta in 1998.” The Komnas HAM

report said

that “security authorities at that time

failed to curb the widespread riots that

took place simultaneously.” The spread of

the riots was a result of a specific policy

based on the “similar pattern at almost

all places where the riots took place, which

began with provocation, followed by an attack

on civilians.”

Shortly before Suharto resigned, Prabowo,

backed by armed men, confronted the Army

Chief of Staff Gen. Subagio at his home.

The next morning Prabowo was removed as Kostrad

commander. Later that day, B.J. Habibie

succeeded Suharto as president, and Prabowo

demanded command of the military. On May

22, he

deployed troops around the presidential

palace. Prabowo

reportedly, “took his demotion badly

– at one point strapping on a sidearm,

summoning several truckloads of troops

and confronting guards at the

presidential palace as he tried to win

an audience” with Habibie. Soon after he

was forced to resign from the military.

In a speech in late 2012

he said, "I am a retired lieutenant

general who once attempted to overthrow

a president. But I failed to do it, and

I regret that I failed."

Recently, while campaigning in Aceh,

Prabowo

offered a vague apology for unnamed

actions his troops took there.

Prabowo was the first person

denied entry into the United States

in 2000 under the UN Convention against

Torture.

After leaving the military Prabowo went

into business and has tried to remake himself

as a populist, becoming president of the

Indonesian Farmers’ Association (HKTI) in

2004, while often arguing that Indonesia

needed a strong, guiding hand - his. The same year, he tried unsuccessfully

to become the Golkar (Suharto’s New Order

party) nominee for President. In 2009 he

was Megawati Sukarnoputri’s vice-presidential

candidate (a PDI-P/Gerindra split ticket).

Until recently, Prabowo led most opinion

polls of declared candidates for President.

Jakarta Governor Joko Widodo (Jokowi), who

officially entered the race in mid-March

as the PDI-P candidate, is the current favorite.

See also

Allan Nairn on

Prabowo

-

Prabowo, Part 3: The NSA, Militia

Terror, Aceh, Servants, and "Slaves"

-

Breaking News:

Indonesian Special Forces, Intelligence,

in Covert Operation to Influence

Election;

Bahasa Indonesia:

Operasi Rahasia Kopassus dan BIN Untuk

Mempengaruhi Hasil Pemilu

-

Prabowo, Part 2: "I was the Americans'

fair-haired boy."

The Nationalist General and the United

States by Allan NairnPrabowo, Bagian 2: “Saya anak kesayangan

Amerika.”

Sang Jenderal Nasionalis dan Amerika

Serikat.

- Part

1: "Do I have the guts,"

Prabowo asked, "am I ready to be called

a fascist dictator?"Bahasa Indonesia:

"Apa saya cukup punya nyali," tanya

Prabowo, "apa saya siap jika disebut

'diktator fasis'?

Wiranto

Wiranto

is another general with deep ties to Suharto’s

New Order regime. He served as Suharto’s

Aide de Camp from 1989-1993. In February

1998, while Indonesia was in the throes

of financial and political crisis, Suharto

named him commander of the Armed Forces

of Indonesia and a month later he was given

the portfolio of Minister of Defense and

Security. Although viewed as a reformer

for his outward support for reducing the

military’s role in politics, he nonetheless

bears responsibility as commander in the deaths

of protesters at the hands of the military

in Jakarta during the May 1998 tumult. Wiranto

was implicated for rights violations in

the

2003 Komnas HAM

report on the anti-Chinese riots in 1998.

As head of the military, there is no doubt

that he was aware – if not involved in the

planning – of the scorched earth campaign

unleashed on the East Timorese following

their vote for independence in 1999. In

February 2003, the UN-backed Serious Crimes

Unit indicted Wiranto

charging him

“with

Crimes Against Humanity for Murder, Deportation

and Persecution in that these crimes were

all undertaken as part of a widespread or

systematic attack directed against the civilian

population of East Timor and specifically

targeted those who were believed to be supporters

of independence for East Timor.” For reason

of realpolitik the government of

Timor-Leste has never followed up on the

indictment.

Wiranto recently

told Al Jazeera

“that he followed state policies [in Timor-Leste]

and that President Habibie was responsible

for those. Habibie rubbishes his claims

and says there are no facts to suggest he

instructed Wiranto and his soldiers to kill.”

He served briefly as Coordinating Minister

of Politics and Security under President

Wahid, but was soon dismissed. Wiranto ran

as Golkar’s vice-presidential candidate

in 1999, Golkar’s presidential candidate

in 2004, and as the party's vice presidential

candidate in 2009.

In 2006 Wiranto established the People’s

Conscience Party (Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat,

Hanura Party), which earned 17 seats on

3.77% of the vote in the last national parliamentary

elections.

See also

Djoko

Santoso

Djoko

Santoso headed the Indonesian military from

2007- 2010 but is less well known than the

above two generals. Some Indonesians view

him as free from the taint of crimes against

humanity (which is setting the bar very

low for electability). He served during

Operasi Seroja, the invasion and occupation

of Timor-Leste, however. He was also put

in charge of the Moluccas region in 2003

in the aftermath of the sectarian violence

there. He

supported censoring

the Australian film Balibo that depicts

the Indonesian military’s murder of foreign

journalists during the beginning of the

invasion of Timor-Leste in 1975. In June

2013 he expressed interest in running for

President. At the time, he said he was considering

running in the Democratic Party’s convention,

which will be held after the parliamentary

elections.

Pramono Edhie

Wibowo

Lieutenant

General (ret.) Pramono Edhie Wibowo is

SBY’s brother-in-law. He was Indonesian

Army Chief of Staff from mid-2011 to May

2013, and is the former head of Kostrad,

the Army Strategic Reserve Command. His

relationship to SBY fueled accusations

of nepotism after his appointment, and

some questioned whether it was a ploy to

shore up SBY’s relationship with the

Indonesian military. Human rights groups

such as Imparsial

have questioned his

human rights record.

Pramono was in Timor Leste in 1999 as head

of Kopassus’ “anti-terrorism” unit. According

to

Masters of Terror,

following the referendum on independence

his unit “slipped into Dili on 5 September

1999, the day before Bishop Belo’s house

was attacked.” The Indonesian government’s

Commission for Human Rights Violations in

East Timor

(KPP-HAM) included him on a list of suspects

warranting further investigation for their

roles in the 1999 violence.

He is running

for the Democratic Party nomination. Despite

his high profile military appointments,

he is not especially well-known or popular.

Pramono’s father,

Sarwo Edhie Wibowo,

was commander of Indonesia’s Special Forces

during the

1965/66 mass killings

and arrests which followed Suharto’s seizure

of power. SBY has generated controversy

by recommending that his father-in-law receive

the official title of “National Hero of

Indonesia.” The bar for that honor is low,

as it includes, for example, military men

who committed terrorist acts against civilians

in Singapore and who were executed for their

crime.

Endriartono

Sutarto

Endriartono

Sutarto is also a former TNI Chief

(2002-2006), as well as former Army

Chief of Staff. During the 1999 period,

he was the Assistant to the Chief of

Staff of the Armed Forces, a key place

in the chain of command, and he

therefore had intimate knowledge of the

Indonesian military’s plans for the

Timor-Leste.

He repeatedly made excuses for violence

by the military and its militia before and after the

1999 referendum. In an

October 2000 interview,

Sutarto said: “It is in the psychology of

our soldiers, because, for so long, they’ve

had links, to work together [with the militias]

to secure East Timor as part of Indonesia.”

According

Masters of Terror,

“In August 1999 Gen Wiranto ordered him

to prepare a contingency plan in the event

of East Timor voting for independence.”

That plan “foresaw with considerable accuracy

the level of destruction and chaos unleashed

after the announcement of the result.” The

plan also “provided a detailed outline of

an evacuation operation and the logistics

required. The code word ‘rise’ (terbit)

was to signal the start of the operation,

and ‘sink’ (tenggelam) its end.” Hundreds

of thousands of East Timorese were forced

into West Timor in the immediate aftermath

of the independence vote.

As a young officer, he was involved in Operation

Seroja and in operations in West Papua.

He received training in the U.S. and UK.

He has been implicated in the kidnapping

and murder of Indonesian labor activist

Marsinah

in 1993. He pushed

for martial law and a greater military

role both in Aceh and in Maluku. While

he was TNI chief, martial law was

imposed on Aceh in 2003, after militia

backed by the military undermined a

ceasefire.

Although Sutarto joined the National Democratic

Party (Partai Nasional Demokrat, Partai

Nasdem) in 2012, he is competing to become

the nominee of the Democratic Party.

See also

Djoko

Suyanto

Air

Chief Marshall Djoko Suyanto was the first

air force officer to serve as Commander-in-Chief

of the Indonesian military (2006-07). He

has served as Coordinating Minister for

Legal, Political and Security Affairs since

October 2009. Unlike other presidential

hopefuls, he has not resigned from his position,

indicating that he is no longer seriously

contemplating a run. He has expressed interest,

however, in becoming the vice presidential

running mate of PDI-P’s Joko Wibowo. He

received military training in the U.S. and

Australia. He has been a fierce critic of

rights supporters in West Papua, including

the official government human rights body

Komnas Ham and KontraS, a leading NGO. He

has denied there are political prisoners

in Papua,

saying that

they are “only criminals who have broken

the law.”

Djoko has also defended the mass killings

in 1965, criticizing

the report of Komnas HAM

that the 1965 purge was a gross human rights

violation. “Define gross human rights violation!

Against whom? What if it happened the other

way around?”

Djoko said in 2012.

“This country would not be what it is today

if it didn’t happen. Of course there were

victims [during the purge], and we are investigating

them,” Djoko added. Paradoxically, in

a speech in Singapore

in December 2012, Djoko warned that Indonesia

did not need a “strongman” with a military

background as president, and he dismissed

polls that suggested former military officers

would do well in 2014: “We must look to

the future and not be tempted to look back

to the past,” he said.

Dino

Patti Djalal does not have a military background

but has defended gross violations of human

rights. A diplomat through most of his career,

he was most recently Indonesia’s ambassador

to the U.S. and prior to that SBY’s spokesperson.

While defending the Indonesian security

forces in East Timor (now independent Timor-Leste)

during the Suharto years,

he would often attack human rights investigators

and organizations. He sought to portray

the violence there as civil conflict among

East Timorese, rather than from repression

of resistance to Indonesia’s illegal and

brutal occupation. In 1999, during and after

the UN-organized vote, Djalal was based

in Timor-Leste as the spokesperson for the

Satgas P3TT (the Indonesian “Task Force

for Popular Consultation in East Timor”).

As Task Force spokesman, Djalal took the

lead in leveling false accusations against

UNAMET (UN Assistance Mission for East Timor).

As ambassador to the U.S., Djalal was key

in arranging the

controversial awarding of Statesman of the Year to SBY by the Appeal to Conscience Foundation.

The foundation says that it works “on behalf

of religious freedom and human rights throughout

the world” and “promotes peace, tolerance

and ethnic conflict resolution.” Many in

Indonesia and abroad said that President

Yudhoyono is

unworthy of the award.

During his time in office, religious intolerance

grew and his government established an unprecedented

discriminatory legal infrastructure.

Djalal is seeking the nomination of the

Democratic Party.

Sutiyoso

Retired

Lieutenant General Sutiyoso is the chair

of the Indonesian Justice and Unity Party

(Partai Keadilan dan Persatuan Indonesia,

PKPI),

a party

founded in 1999 by a group of retired

senior Indonesian army officers from the

Suharto period. He is the former

Governor of Jakarta. While he is not

running for president, he has expressed

interest in running for vice president

with PDI-P’s Jokowi. He received

training from the U.S., Australia and

UK.

Sutiyoso was a captain in 1975 and part

of the Indonesian special forces team involved

in the attack on Balibo. In 2007, he visited

Australia. When

his testimony was sought

by an official coroner’s inquest in Sydney

investigating the deaths of journalists,

he

quickly fled

the country.

In addition to his involvement in the illegal

invasion of Timor-Leste, he served in Aceh,

and stands

accused of involvement

in “the summary execution of thousands of

alleged gangsters in Jakarta.” He was Jakarta

military commander when thugs backed by

troops and police

attacked the headquarters

of the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI)

in 1996.

Its head, Megawati Sukarnoputri was replaced

by someone more favorable to the regime.

Former pro-independence fighters in Baucau,

Timor-Leste, “accused

Jakarta Governor Sutiyoso

of conducting regular torture sessions there

in the 1970s.”

|

Order

from Amazon,

Support ETAN |

|

|

|

|

|

About ETAN

The

East Timor and Indonesia

Action Network

(ETAN) was founded in 1991. ETAN supports

democracy, human rights and justice in Timor-Leste,

West Papua and Indonesia. ETAN is non-partisan.

It works on issues and does not support

candidates or political parties in any country.

Website:

www.etan.org

Twitter: @etan009.

|